by H. L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan

[From “Clinical Notes”, The American Mercury 3(11):314-317 (1924-11)]

The National Hymn.–The pacifist, when all other devices fail them, attack “Star-Spangled Banner.” This great choral, they argue, is full of brimstone and braggadocio—a direct incitement to militarism. It depicts the Republic as the land of the free and the home of the brave, and so arouses a truculent and bombastic spirit. One of the principal exponents of this View is a lady Christian Scientist of great wealth. She takes whole pages in the New York papers to advocate the adoption of a more modest and temperate national anthem—something, say, on the order of “Lead, Kindly Light” or “Nearer, My God, to Thee.” Her position, it seems to me, is very unsound; I suspect, indeed, that she has never read “The Star-Spangled Banner.” If she were familiar with its text she would know that it is not bombastic at all, but very moderate and even timorous. The first stanza, which is all that anyone ever hears, actually ends with a question mark. The poet is not at all sure that the Republic will survive. He sees it beset by formidable enemies and is in obvious doubt. All he says directly is that it would be a pity for so meritorious a nation to come to grief. It is loving fear for it rather than boastful pride in it that makes him call it the land of the free and the home of the brave. His phrase is a device of rhetoric, like that employed by a curb broker or university president when he calls Dr. Coolidge a great man.

Of the other three stanzas only one shows anything properly describable as a bellicose spirit, and that is the second. It is devoted mainly to reviling the enemy. Well, why not? That enemy, when “The Star-Spangled Banner” was written, had but lately Captured Washington, burned the Capitol, and driven the President and Congress to the woods of Rock Creek. When I was a boy, before the Sulgrave Foundation had got into action, the tale of its atrocities was still in all the school-books. Every American youth of the 80’s was taught to hate the Huns of 1814. That Francis Scott Key did so is certainly not to be wondered at, for despite his professional immunity as a poet he had been seized bodily, carried to the fleet of the Potsdam tyrant, and there exposed to the musket and shell fire of his own people. Yet notwithstanding this gross provocation he devoted but one of his four stanzas to billingsgate. Of the others, one, as I have said, ends with a question mark. The remaining two are even milder. One is mere prosodic burbling: a stanza almost devoid of logical content. The other is full of discreet ifs. If “our cause is just”—“then conquer we must.” If we continue to trust in God, all will be well. But not, apparently, otherwise.

All this leads to the inevitable conclusion that “The Star-Spangled Banner” is not actually too raucous and boastful, as the pacifists allege, but too pianissimo. If it deserves censure at all, it is because it does discredit to a free and proud people by representing them as too mild and hesitant. “lf our cause is just,” forsooth! Our cause is always just ipso facto. To question it, in these days of Ku Kluxes and American Legions, is far worse than to dodge serving it. The first duty of the American citizen is to assume that his country is never wrong; his second is to enforce that assumption upon all dissidents by brute force. It is, indeed, already a fixed principle of our jurisprudence that such dissidents have no rights—that it is competent for any citizen to have at them at sight, and without trial. As time passes, that doctrine, no doubt, will be extended. That is to say, it will begin to take in, not only national policies, but also the whole body of communal mores. It will then become unlawful, and punishable by death, to read Marx, Nietzsche or Darwin, just as it is already unlawful, and punishable by imprisonment, to use alcohol in the immemorial manner of civilized men.

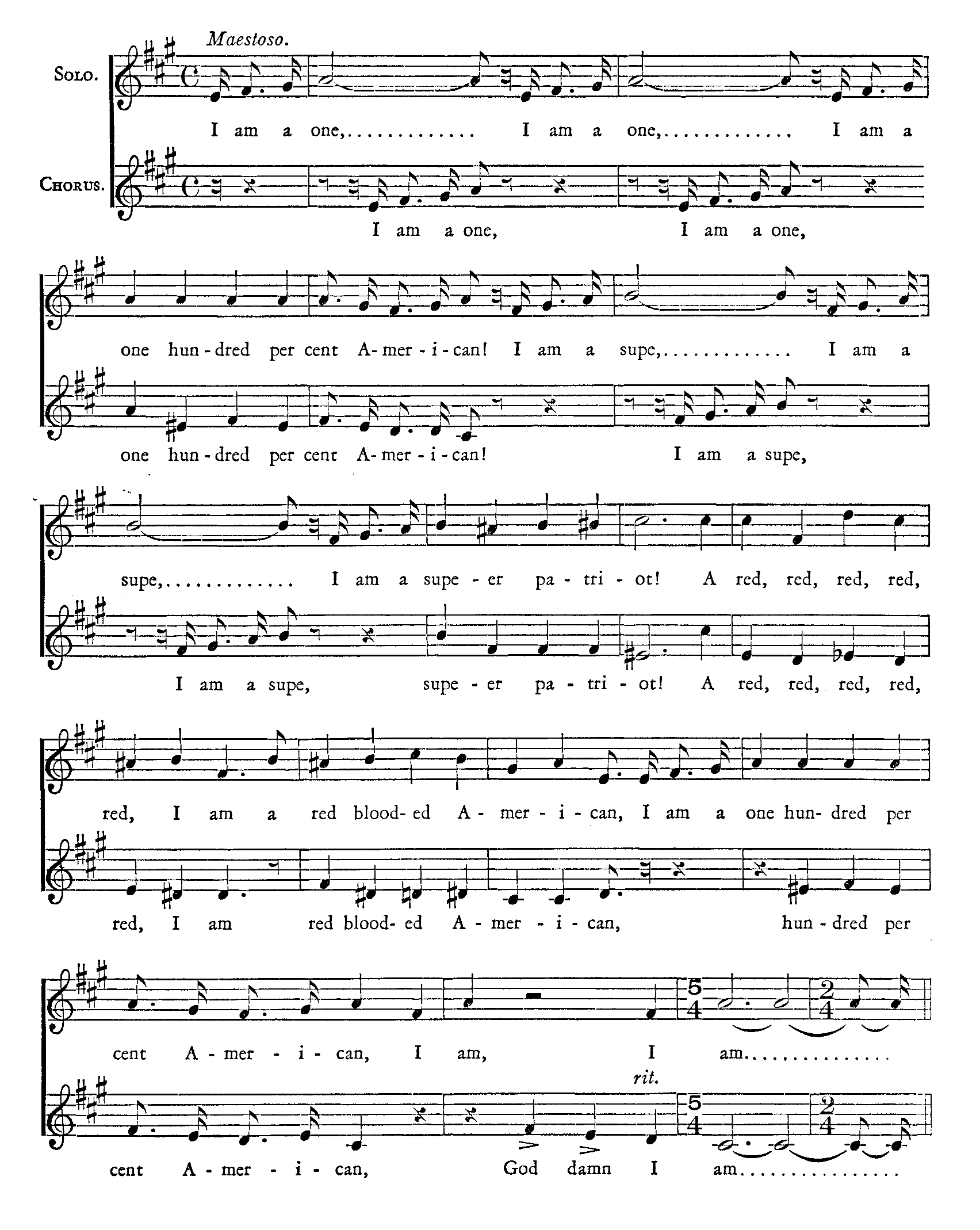

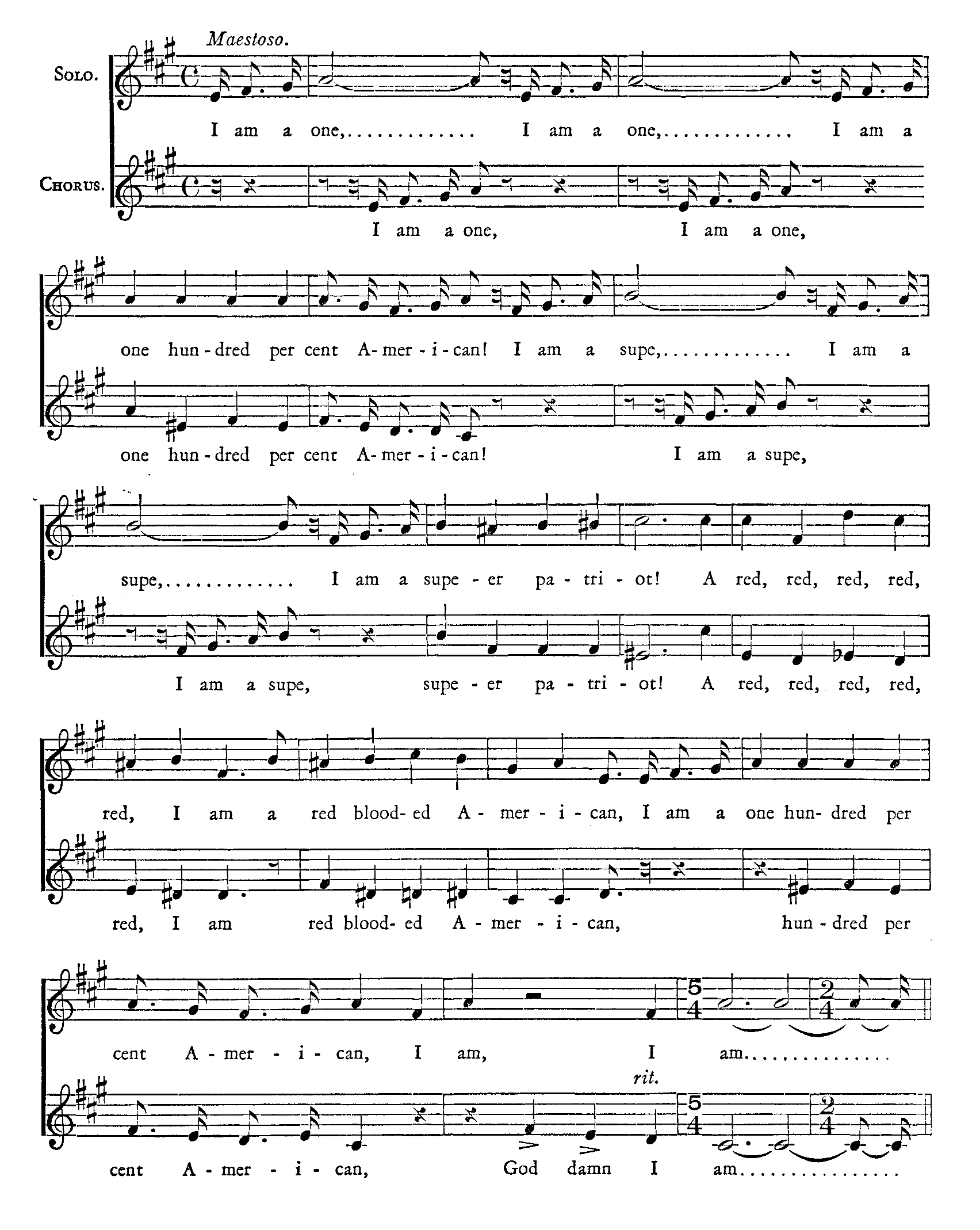

What is needed is a national anthem to voice the new spirit of 100% Americanism, as “The Star-Spangled Banner” voiced the feeble hesitations and uncertainties of Key’s time. This anthem must be bare of all ifs and buts; it must be an exultation rather than a hymn; it must cover the whole glittering and inspiring spectacle of American national life; the national spirit must be in every line of it. Great talent must be thrown into its composition; its production will be no job for a common poetaster, with his pale emotions and his Greenwich Village theories. Great talent, indeed, has been thrown into its composition, for it already exists, words and music. And here it is:

The author is Poet W. W. Woollcott, of the Maryland Free State. History will remember him. For his anthem has every merit and no defect. It is vigorous in rhythm, it is facilely singable (which “The Star-Spangled Banner” surely is not), and in its text there is the true soul of latter-day America. You will find no un- certainty there, but only conviction. The poet says what he has to say in plain language: let Europe take heed. Only once does he ameliorate his stark forthrightness, and then it is by a device of humor—in the line beginning “I am a red.” A waggish touch—and a pleasant signal for dropping the concrete Red into the tar-pot. The other stanzas, of which there are twenty, are all in the same tone. I append three:

||: For I am just,:||

||: For I am just,:||

For I am just folks, yes, that’s just what I am;

||: I like to read,:||

||: I like to read,:||

I like to read the Saturday Evening Post.

In art I pull no high-brow stuff,

I know what I like and that’s enough;

I am a one hundred per cent American,

I am,

God damn!

I am!

||: How can the un-,:||

||: How can the un-,:||

How can the Unknown Soldier rest in peace,

||: While the vile Hun:||

||: While the vile Hun:||

While the vile Hun still has his beer?

Under Wayne B. Wheeler’s (attorney, general counsel and head lobbyist for the National Anti-Saloon League) flag unfurled

We’ll carry Prohibition around the world

I am, etc.

||: I am an ant-,:||

||: I am an ant-,:||

I am an anti-Darwin intellectual;

||: The man who says,:||

||: The man who says,:||

That any nice young boy or gal

Is a descendant of the ape

Shall never from hell’s fire escape.

I am, etc.

Mr. Woollcott dedicates his anthem to the Rotary International, the Better America Federation, the Dawes Minute Men, the Department of Justice, the American Legion, the Invisible Empire, the Methodist Episcopal Church South, the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, the Kiwanis Club International, the Ancient Arabic Order of Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, and the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States. He has refused to apply for a copyright on it. It may be performed or reproduced by any American, at all times and everywhere. It is, like Grant’s Tomb and the Yellowstone National Park, the perpetual property of the native-born, free, white, Protestant people of the United States.